|

| Image © Thames & Hudson |

Introduced by Richard I. Vane-Wright. Produced in partnership with Oxford University Museum of Natural History.

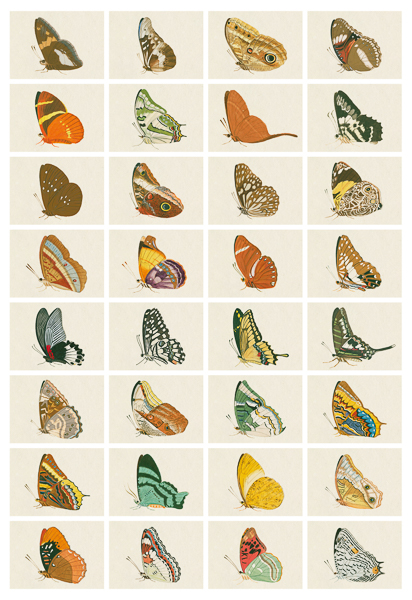

Jones's Icones contains finely delineated paintings of more than 760 species of Lepidoptera, many of which it described for the first time, marking a critical moment in the study of natural history. With Iconotypes Jones's seminal work is published for the first time, accompanied by expert commentary and contextual essays, and featuring annotated maps showing the location of each species.

Jones painted the species between the early 1780s and 1800, drawing from his own collection and the collections of Joseph Banks, Dru Drury, Sir James Edward Smith, John Francillon, the British Museum and the Linnean Society. For every specimen painting he provided a species name, the collection from which it was taken and the geographical location in which it was found. In 1787, during a visit to London, the Danish scientist Johann Christian Fabricius studied Jones’s paintings and based 231 species of butterfly and moths on them. In this enhanced facsimile, Jones’s references to historic references are clarified and modern taxonomic names are provided, together with notes on which paintings serve as iconotypes. Contextual commentary by specialist entomologist Richard I. Vane-Wright gives an account of Jones's life and his motivation for collecting butterflies and creating the Icones, and evaluates the significance of his work. Interspersed at intervals between the pages of Jones's paintings are modern maps showing the location of each species painted, and expert essays on the development of lepidoptery and taxonomy after Linneaus, and the roles of collectors and natural history artists from the late 1700s to mid-1800s.

I am very fortunate to have paid numerous visits to the Oxford University Museum of Natural History, where the staff have been very generous in providing me with 'behind the scenes' access to what I can only describe as a 'treasure trove'. One of their treasures is the original manuscript of William Jones' seven-volume masterpiece, Icones, and I'm absolutely delighted to see that this work is now reproduced to a high quality in Iconotypes (think of an 'Iconotype' as a type specimen before the binomial naming system was introducted by Linnaeus). Icones is truly an historic piece of work, containing paintings of the Lepidoptera available to Jones between the 1780s and 1800 - an age of exploration and global trade with specimens returning from all parts of the world. Jones, a wealthy wine merchant, was well-connected and his Icones illustrates specimens from his own collection as well as those of Dru Drury, Joseph Banks, John Francillon, Sir James Edward Smith, the British Museum and the Linnean Society. The result is an extensive and beautiful compendium of world Lepidoptera (almost all butterflies) known at that time and Iconotypes will sit proudly on the shelf of any Lepidoptera enthusiast.

Each volume of Icones covers a different species group, with Iconotypes including several very useful maps that show the origin of each of the 856 illustrated species. Although not shown in this review, each plate from the original Icones is complemented with an up-to-date analysis of each species shown, including the source of the specimen, the modern binomial name and world distribution. Useful side notes are also shown against each species where appropriate.

|  |

However, Jones' plates are just one aspect of Iconotypes - the book also includes a foreword by Paul Smith (Director of Oxford University Museum of Natural History), an extensive introduction and conclusion from the well-known entomologist Richard (Dick) Vane-Wright, and several articles that are to be found between the volumes. These additional sections are particularly insightful - for example, Vane-Wright explains how Jones' analysis of wing veination directly contributed to improving species classification. The various articles (and their authors) are:

What I really liked about these articles is how they weave together the elements of science and art that were prominent in the work of leading 18th century Lepidopterists and, of course, Jones in particular. Collectively, these articles provide a thorough and fascinating history lesson, transporting the reader to a period when the interest in Lepidoptera was increasing exponentially.

While Iconotypes will justifiably receive the praise it deserves, there are a few errors in the material that has been added to Jones' Icones, which did distract me on occasion. For example, a High Brown Fritillary specimen is used for Semele (Grayling) and a Silver-washed Fritillary for High Brown Fritillary. A plate of 'Butterflies no longer found in the British Isles' does not emphasise that it is the subspecies or race shown that is extinct (such as Scotch Argus from Yorkshire and the cretaceus subspecies of Silver-studded Blue), or that it is the English population of Chequered Skipper that is extinct (since this species is alive and well in Scotland). Also, the Heath Fritillary (shown on a plate as 'Pearl bordered likeness' and with the correct scientific name of Melitaea athalia) is identified as a Pearl-bordered Fritillary.

These quibbles aside, my conclusion is that any enthusiast that is interested in world Lepidoptera (butterflies in particular) and its historical backdrop will absolutely love Iconotypes and, as such, this new work is highly recommended. I leave you with Richard Vane-Wright's own summary of this work, followed by a number of mouth-watering plates! ... "Jones's Icones has excited interest and admiration among a privileged few for more than two centuries ... the Icones can now be seen in a wider perspective. These paintings come from a time when the unity of art, science and aesthetics was rarely, if ever, questioned. Arguably, the greatest value of the Icones lies in its intrinsic worth as another of those priceless legacies that reflect human curiosity, passion, skill and creativity".