Abstract: The presence of the Mountain Ringlet (Erebia epiphron) in Ireland has been a topic of much interest to Lepidopterists for decades, partly because of the small number of specimens that are reputedly Irish. This article examines available literature to date and includes images of all four surviving specimens that can lay claim to Irish provenance. [This is an update to the article written in February 2014].

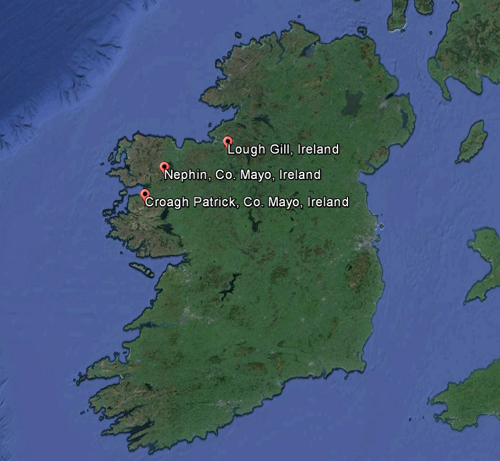

The presence of the Mountain Ringlet (Erebia epiphron) in Ireland has been a topic of much interest to Lepidopterists for decades, partly because of the small number of specimens that are reputedly Irish. The Irish Mountain Ringlet is truly the stuff of legend and many articles have been written over the years, including the excellent summary by Chalmers-Hunt (1982). The purpose of this article is to examine all relevant literature and, in particular, the various points of view that have been expressed over the years. This article also includes images of all four surviving specimens that can lay claim to Irish provenance and some of the sites mentioned in conjunction with these specimens are shown in Figure 1.

|

| Figure 1 - Key Sites |

The first reported occurrence of Mountain Ringlet in Ireland was provided by Edwin Birchall (Birchall, 1865) where, using a previous scientific name of Erebia cassiope, he writes:

"The only Irish locality for this insect, about which I can speak from my own knowledge, is Croagh-Patrick, near Westport; in some marshy hollows about halfway up the mountain, I took a fine series in June 1854; but most likely it would also be found on the Nephin range, and I have reason to believe it occurs on Slieve-Donard, near Ross Trevor."

Birchall (1866) provides further tantalising details of the Croagh-Patrick locality:

"The locality for this species is about halfway up the mountain on the Westport side, in a grassy hollow where a little hut is erected for the shelter of the pilgrims. I captured a fine series here in June 1854."

One of Birchall's specimens can still be found in the Lepidoptera collection housed in the National Museum of Ireland, in Dublin, and is shown in Figure 2.

|

| Figure 2 - The Birchall Specimen Image © National Museum of Ireland |

Birchall also mentions other potential localities, in the Nephin range (in Co. Mayo in the west of Ireland) and Slieve-Donard (in the Mourne Mountains, Co. Down, in the east of Ireland). Slieve-Donard is the highest mountain in Northern Ireland at 2,790 feet (850m) and is actually closer to the town of Newcastle than Rostrevor (which is the modern spelling of Ross Trevor mentioned by Birchall).

Donovan (1936) suggests a second Birchall specimen in existence, although its whereabouts, today, are unknown: "Mr. Dudley Westropp informs me he possesses one labelled 'E. Birchall', which he got from Thornhill, but is uncertain of the exact locality". Given that Birchall took "a fine series in June 1854" (Birchall, 1865), it would not be surprising that some of that series was passed on to other entomologists. "Thornhill" is a reference to W.B. Thornhill who Beirne (1985) identifies as an entomologist who was based in Co. Louth.

In analysing the origins of the Irish Mountain Ringlets, Redway (1981) questions Birchall's integrity as a whole, thereby casting doubt on the authenticity of Birchall's Irish Mountain Ringlet. Redway starts by quoting Birchall (1866) where we find the following stated under Argynnis lathonia (Queen of Spain Fritillary):

"Argynnis lathonia. Killarney, in the lane leading from Muckross to Mangerton, near a limestone quarry on the left of the road, August 10, 1864."

Redway goes on to say that Kane (1893) refers to this record, adding "seen on the wing", and this therefore suggests that Birchall was not as honest as he could have been with his record. Redway goes on to quote Donovan (1936) who says "In my opinion, Killarney, especially the quarry aforesaid, with which I am familiar, is the very last place to find an immigrant like lathonia". At the time of writing his article, Redway claims only a single validated record of lathonia existed, from Co. Waterford in 1960. Redway concludes his scathing attack on the Birchall Irish Mountain Ringlet record as follows:

"My own belief is that these records are Birchall's own embellishments of what would otherwise have remained as mere hearsay accounts, accounts which left that man fairly satisfied though not truly positioned for convincing others. By giving such a precise description of the whereabouts of the sightings, he hoped to encourage lepidopterists to follow up the stories which were not, in fact, as complete as he would have had his readership believe. This applies as much to lathonia as to epiphron if it be assumed that the status (whether resident or migrant) of that butterfly was at that time subject to dispute.

Whatever the origin of Birchall's epiphron specimens, however, no doubt remains in my own mind that they did not emanate from Croagh Patrick. The (Birchall) male on display in Dublin museum I could not separate from my own English Lake District examples. Is this just a coincidence?"

Of all of the specimens found in the National Museum of Ireland, Dublin, the male labelled "Croagh Ptk? Fetherston H. 64.97" has received the least attention. Donovan (1936) refers to this specimen as "labelled Croagh Patrick, Fetherstonhaugh Coll.", suggesting that this came from the collection of Dublin-based entomologist Stephen Radcliff Fetherstonhaugh. Indeed, the numbers on the data label are the registration number of the specimen when Fetherstonhaugh's collection was acquired by the National Museum of Ireland in May 1897 (O'Connnor, 2013. pers. comm.).

|

| Figure 3 - The Fetherstonhaugh Specimen Image © National Museum of Ireland |

It is not known if Fetherstonhaugh caught this specimen himself or whether Birchall gave Fetherstonhaugh one of his specimens since, as shown in Tutt (1896), Birchall is known to have given Fetherstonhaugh specimens of other species. Fetherstonhaugh was also a friend of W.F. de Vismes Kane who is also known to have Mountain Ringlet specimens in his possession, as discussed later in this article. Dr. Jim O'Connor of the National Museum of Ireland believes the Fetherstonhaugh specimen to be a genuine Birchall specimen (O'Connnor, 2013. pers. comm.).

Following Birchall's discovery in 1854, Carpenter (1895) reports on the "rediscovery" of the Mountain Ringlet in Ireland some 40 years later (in 1894) by Rev. R.A. McClean, using the name cassiope which was (at the time) used to describe the form found in the British Isles:

"I am glad to be able to record the rediscovery of this mountain butterfly in Ireland. For forty years, since the late Mr. Birchall took "a fine series in June, 1854 ... about halfway up Croagh Patrick on the Westport side in a grassy hollow," no entomologist has seen the species in this country. The captor of this specimen now recorded is the Rev. R.A. McClean, late of Sligo, the greater part of whose valuable collection of lepidoptera has been secured by the Dublin Museum. He informs me that he took the insect on the edge of a wood at Rockwood near Sligo, at the height of about a thousand feet, during the summer of last year (1894). A high wind was blowing at the time, and he believes that the butterfly had been blown down from higher ground. The specimen is a female somewhat rubbed, the wings expanding 1 1/2 inches, and with the fulvous markings and black spots rather clearer than in most of the British specimens of var. cassiope in the Museum collection.

As this locality is about fifty miles from the previous station for the insect (Croagh Patrick, Co. Mayo), we may hope that the species has a fairly wide distribution among our western mountains, though it is doubtless excessively local. Like many other alpine insects, it ranges much further south in Ireland than in Great Britain, where it is known from the hills of Scotland and Cumbria, but not those from Wales. On the continent it is found in the Alps, the Pyrenees, and the mountains of Hungary, while the type of epiphron occurs in the mountains of Germany and northern France."

Rockwood is a hill south of Lough Gill, Sligo which, according to Graves (1950), is "970 ft. in height above Slish Wood (Ref. Ordnance Map 1/2" to one mile, Sheet 7, Sligo, 7D and 7E)". McClean's specimen can also be found in the Lepidoptera collection of the National Museum of Ireland in Dublin.

|

| Figure 4 - The McClean Specimen Image © National Museum of Ireland |

Kane (1901) provides new information on the locality where the McClean Mountain Ringlet was found, although he gives no details of the origin of this information or why it only came to light six years after the original description was provided by Carpenter (1895). In addition, the eastern shores of Lough Gill are not in Co. Sligo but Co. Leitrim, thereby casting doubt on Kane's statement:

"One specimen, in a collection of the Rev. R. McClean is believed to have been taken on the hilly slopes on the eastern shores of Lough Gill, Sligo."

Graves (1950) makes a further observation on the exact location of the McClean Mountain Ringlet some 49 years later, referring back to the original location specified by Carpenter (1895). By making no mention of Kane's comments, Graves is, in essence, dismissing them.

"In his Practical Hints for the Field Lepidopterist (Part II, p.78) that distinguished entomologist, J.W.Tutt, after a reference to Birchall's well-known description of the locality on Croagh Patrick where he took Erebia epiphron "in June, 1854." continues - "It has also been recorded from the edge of a wood at Rockwood near Sligo at about 1,000 feet elevation." I have reason to believe, from information kindly given to me by Mr. A.W. Stelfox, that the butterfly was not taken by the Rev. R. McClean on the summit of the hill 970 ft. in height above Slish Wood (Ref. Ordnance Map 1/2" to one mile, Sheet 7, Sligo, 7D and 7E) as Tutt's record would suggest, but on the west side of the hill nears its foot and close to the road from Sligo to Dromahaire about one mile south of Lough Gill. The butterfly had presumably been blown down or had strayed down from a higher elevation. Kane probably knew where McClean had taken this specimen but suppressed details, as was often his practice. He need not have feared "over-collecting" in Ireland! It seems to the writer that a young and active collector with the use of a car and based on Sligo might do worse than explore the Ox Mountains (the range of hills south of Lough Gill and the Ben Bulbin-Truskmore section of the Dartry Mountains) in late June and early July in search of this elusive butterfly which has not been taken in Ireland since Kane found it on Nephin in 1900 or 1901 (Catalogue of the Lepidoptera of Ireland, p.155)."

Redway (1981) questions the validity of the McClean Mountain Ringlet on several fronts. In doing so, he makes reference to the subspecies aetherius (Esper, 1805), form nelamus (Boisduval, 1840) which is found in the Alps and to which the Irish Mountain Ringlet specimens have been compared (as discussed later in this article):

"What was this alpine butterfly doing so near sea level? Who actually took the specimen? Why could the captor not recall the locality (in County Leitrim, not Sligo, if it really was taken at the eastern end of Lough Gill)?"

All of Redway's questions are answered by Carpenter (1895) and it is therefore surprising that they are asked. "What was this alpine butterfly doing so near sea level?" - because "A high wind was blowing at the time, and he [McClean] believes that the butterfly had been blown down from higher ground". "Who actually took the specimen?" - McClean. "Why could the captor not recall the locality (in County Leitrim, not Sligo, if it really was taken at the eastern end of Lough Gill)?" - McClean recalled the locality as "on the edge of a wood at Rockwood near Sligo". All in all, Redway's attempt to discredit the record seems unfounded.

In posing this last question, Redway is clearly referring to the claim by Kane (1901) that the specimen was "taken on the hilly slopes on the eastern shores of Lough Gill" which is later corrected by Graves (1950). Nash (2012) confirms that a sighting at the location given by Kane (1901) is unlikely:

"Canon R McClean's location which has been stated as "being on the hilly slopes near the eastern shore of Lough Gill" (= Leitrim, not Sligo) is considered improbable."

Available literature is sprinkled with attempts to relocate the Mountain Ringlet in Ireland. W.F. de Vismes Kane provides a summary of his first attempt in "A Catalogue of the Lepidoptera of Ireland" (Kane, 1893), published in The Entomologist in 1893, where he starts by quoting Birchall:

"Croagh Patrick near Westport, Mayo. "The locality for this species is about half-way up the mountain on the Westport side, in a grassy hollow, where a little hut is erected for the shelter of the pilgrims. I captured a fine series here in June, 1854 (B.)". I have seen no Irish specimens, nor have I heard that any visit to the above locality has been made since for that purpose. It would seem probable that other habitats may be found for the species on the range of mountains extending from Achill towards Nephin. Were it not that the alpine flora and entomological fauna have not usually, so I understand, a parallel distribution in Ireland, we might expect that the heights of Slieve League, Benbulben, and Mount Brandon, would reward an entomologist by interesting discoveries in this direction."

However, Kane published a supplementary list to his catalogue in The Entomologist in 1900 (Kane, 1900):

"Since writing my notice of this butterfly, and suggesting that the mountain range from Achill to Nephin might very probably yield habitats, I have been fortunate enough to meet with a few specimens on the Nephin. The bad weather and subsequent engagements have prevented my investigating the locality further."

Kane's papers from The Entomologist were published in a single volume in 1901, entitled "A Catalogue of the Lepidoptera of Ireland" (Kane, 1901). Kane (1912), in the Clare Island Survey, clarifies the exact date of his visit and confirms that he took a single specimen:

"Visits to Croaghpatrick were made during the first half of June in 1909 and 1910 in the hope of again finding the alpine butterfly Erebia epiphron, recorded by Birchall in 1854; but though the locality indicated by him was carefully and exhaustively examined by Mr. Wyse and myself, no specimen was seen. The sunless weather and chilly wind probably account for our failures. My capture of a specimen on Nephin on 9th June, 1897, however, proves its survival on the Mayo mountains, but it only flies in bright sunshine."

Redway (1981) questions the validity of Kane's claims:

"It was certainly no accident that he [Kane] shunned Croagh Patrick, still at that time so greatly under-explored and apparently so long unvisited by a lepidopterist. Moreover, this new account of his leaves a great deal to be desired as, apart from the fact that no specimens were taken, there is no reference to elevation, situation, proximity or even the year in which the visit was made."

However, Paul (1985) dismisses Redway's challenge on the basis that Redway was unaware of Kane's most recent elaboration of his search at Croagh Patrick and subsequent capture of a specimen on Mount Nephin:

"The above [Kane's report in the Clare Island Survey for 1912] is important when considering that Redway's criticism of Kane's record is based on the lack of knowledge of the date and capture of the Nephin specimen".

The Kane specimen, in particular, raises the question of flight period, given the relatively-early date of 9th June. While the Mountain Ringlet found in Cumbria (which is at a similar latitude to the Nephin) peaks in the second half of June, there are certainly some years where it appears much earlier and, therefore, the date given by Kane does not seem unreasonable and has never been questioned by any authority.

As it happens, three Kane specimens reside in the National Museum of Ireland in Dublin, all without location data and all labelled "Coll. Kane 1903". Since Kane only claims to have capture a single specimen, it is unlikely that any of these specimens, which all have the same data label, are the specimen that Kane captured on Nephin. Donovan (1936) states equivocally that "There are no samples of Kane's Mount Nephin Erebias in the National Museum, Dublin". Nash (2012) provides an insight into the origin of these specimens:

"It should be remembered that Kane travelled widely and may well have collected specimens when he was working on his European Butterflies."

As described in Nash (1990), a discovery in 1990 by Robert Nash and Chris Samson of Ulster Museum in Northern Ireland resulted in a new reputedly-Irish Mountain Ringlet, presumed to be from 1918, adding to those of Birchall, McClean and Fetherstonhaugh, although no locality is given:

"The specimen, a female, was discovered amongst tropical Pieridae and Irish Marsh Fritillaries. (Euphydryas aurinia (Rottemburg)) in a sale of damaged stock at Watkins and Doncaster, Hawkshurst, Kent. The upper label reads "Irish 30.6.18" the lower label either "1315" or, more likely, "BW". Although the history of the specimen is obscure there is no reason to suspect its authenticity. It is now in the collections of the Ulster Museum."

|

| Figure 5 - The Fourth Surviving Mountain Ringlet Specimen Image © National Museums Northern Ireland |

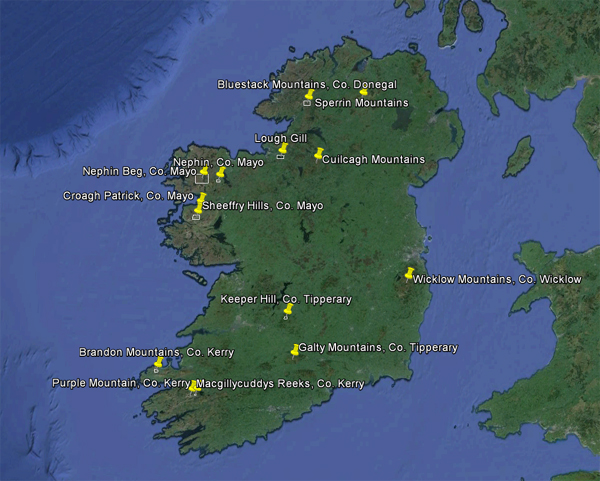

Unsurprisingly, several individuals have attempted to relocate the Mountain Ringlet in Ireland, but the repeated attempts of Raymond Haynes are worthy of note, as described in Haynes (1955), Haynes (1956a) and Haynes (1956b). Haynes catalogues not only his own failed attempts, but also those of others, and these are included in the summary below. The map below provides an indication of the location of some of the sites mentioned.

|

| Figure 6 - Searched Sites |

Warren (1936) attributes the small number of very dark Irish specimens to the subspecies aetherius (Esper, 1805), form nelamus (Boisduval, 1840), which is found elsewhere only at high altitude in the Alps. This form is less strongly marked than populations in Scotland and Cumbria and the orange band, found only on the forewings, is faint and contains indistinct spots:

"This little form, which in size averages male 30-34, female 34-38 mm., is distinguished from [form] aetherius by the loss of markings both upper- and underside. On the upperside the band on the forewings is replaced by a few indistinct spots, usually so blurred as to appear only as a reddish-brown shade in the ground-colour; figs. 778 male, and 773 female, are strongly marked specimens for this form. The black spots are reduced to two tiny points at the apex of the forewing; very frequently there are none. The hindwings are without markings either upper- or underside. The extent of the band markings on the forewings, upperside, is most variable: from specimens like those figured where traces of five spots exist, they range to absolutely unmarked examples. Perhaps the most usual form is that in which the spots are indicated only at the apex of the wing."

Warren (1936) specifically refers to the Irish specimens:

"Essentially a high-level form in the Alps ... There can be no doubt that the centre of its range lies in the Grisons and the neighbouring mountains of the Tyrol and Dolomites. Considering this, it is strange that the only reputed Irish specimens of epiphron known to me, three in number, in the National Museum in Dublin, seem, undoubtedly, to belong to this form. I know these specimens only from photographs of two of them, one of which is shown by figs. 772 and 779 [the Fetherstonhaugh Mountain Ringlet]. Both photographs were good, and there was no room to doubt that the Irish specimens were nelamus. There was obviously no connection with English mnemon. A good series of Irish specimens would be of great interest, if they could be obtained, for from the isolated position their habitat it would not be surprising if they proved to be a more distinct race than the few specimens suggest. Ireland is, of course, the most westerly station of the species."

Despite the small number of Mountain Ringlet specimens that can lay claim to Irish provenance, I personally see no reason to suspect their authenticity. The concerns expressed by several authorities do not, in my opinion, provide sufficient evidence to support an alternative view. However, the presence of the Mountain Ringlet in Ireland will always remain contentious unless some enterprising and serendipitous lepidopterist locates an as-yet-undiscovered colony.

I would like to thank Dr. Jim O'Connor (National Museum of Ireland) and Angela Ross (National Museums Northern Ireland) for providing access to the museum specimens that have been illustrated in this article. I would also like to thank Dr. Brian Nelson and Robert Nash for locating the fourth surviving Irish specimen within its collection, as well as Ian Rippey (Butterfly Recorder for Northern Ireland) for his extensive and invaluable input on the subject. Finally, I would like to thank Katherine Child of the Oxford University Museum of Natural History for assisting with the digital processing of the specimen images.