|

| Image © Peter Eeles |

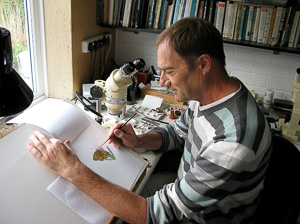

Pete:

Richard, great to finally meet up with you! So how did your interest in both wildlife and art come about?

Richard:

Both came from my dad really - he was keen on butterflies and moths, and before him, my grandad, who had a small collection of butterflies and moths. That was the first place I headed for when I went to see him.

Pete:

Speaking of your dad - I believe he's one of the men figured in the Commando Memorial near Spean Bridge (a well-known site for Chequered Skipper)?

Richard:

My dad was a commando, a real tough bloke who presumably had the right look, so they got him to pose for the commemorative statue, which is situated close to where the commandos trained at Fort William. He's the one at the front looking towards Ben Nevis. It's strange to think, given his love of butterflies, that the Chequered Skipper was discovered in the area at around the time he was training there.

|

| The Commando Memorial near Spean Bridge Image © James Dorrian |

It must have seemed a bit odd for a big tough bloke to be keen on butterflies. There was an account of him in a book on the commandos called "Swiftly they Struck" where his comrades thought he'd gone berserk during an episode when, while sheltering in a trench in France, he jumped out to chase after a Camberwell Beauty!

|

| Extract from Swiftly they Struck |

My dad also encouraged both my brother and me to draw. We used to go out birdwatching and butterflying with him and that influence has been there ever since. I eventually went to art college and did graphic design but wasn't that enthused about designing baked bean cans and packets of cornflakes. Toward the end of the course I concentrated on illustration, which I liked much more. I particularly enjoyed any association with natural history since the subject matter is so vast - not just insects but also skulls, birds, fossils, mammals and the like. When I left college I worked in a design group for six months in the only "proper" employed job I've ever had, while at the same time doing some freelance work for an agent. I eventually became self-employed and have been self-employed ever since. The agent brought me quite a bit of work in, much of it in advertising, but also some book illustration, which I much preferred - it was far more satisfying. Although advertising paid better than illustrating wildlife books, I decided to stick with the book illustration and have been poor ever since!

The very first book I contributed to, as a freelance illustrator, was the Reader's Digest Book of the Countryside, in the 1970s, not long after I'd left college. It contained various sections and I was asked to do the insects. After that, the first butterfly book I illustrated was "Butterfly Watching" in 1980 with Paul Whalley of the Natural History Museum. I followed that up with the Mitchell Beazley Pocket Guide to Butterflies, also with Paul Whalley, in 1981. Through these publications I became "type cast" as an illustrator of insects and the more I did, the more work I managed to get! I've been doing them ever since!

Pete:

So who were your earliest influences?

Richard:

Frohawk was a definite influence, but later on when I started working, I used to frequently visit the Natural History Museum. There was an entomological artist there called Arthur Smith, who did some of the Tortricidae in the two volumes of British Tortricoid Moths (Bradley, Tremewan and Smith) and I always thought he did some wonderfully detailed work. And before him there was an artist called Amedeo Terzi who, again, did some fantastic work. And when I say fantastic, I mean in terms of detail and accuracy. Arthur Smith had a lovely technique of half tone and line drawings. Both were employed by the Natural History Museum as illustrators and had the luxury of time, since they were employees! Unfortunately, although I like to spend as much time as I can on my work, I'm self-employed and also have to make a living from it!

Pete:

So how long, on average, does it take you to produce one of your paintings, or is it a case of "how long is a piece of string"?

Richard:

This is the question I'm most often asked! A plain butterfly with comparatively little detail, such as a Small White, will obviously take much less time than, say, the underside of a Painted Lady. But paintings that show a portrait of a butterfly on a plant, take on average a couple of days. Of course, some time is spent determining layout and composition, and if I'm working with specimens and photos, I might choose to show the butterfly on a different plant to make a more pleasing illustration - so those decisions take time. I might also go into the countryside and bring a bit of vegetation home (or photograph it) and include that in the painting.

Pete:

You've had quite a few collaborations - Butterflies of Britain and Ireland (with Jeremy Thomas), the Collins Butterfly Guide (with Tom Tolman), The Moths and Butterflies of Great Britain and Ireland ("MOGBI", with Maitland Emmet and John Heath), the Field Guide to the Moths of Great Britain and Ireland (with Paul Waring and Martin Townsend) as well as dragonfly-related books. The book with Jeremy is quite superb.

Richard:

The book with Jeremy went particularly well since he's such a good writer and we got on well together. Although we weren't too happy with the front cover, which was designed by the publishers and was intended to resemble a glass-topped drawer from a cabinet full of specimens, which really defeated the whole purpose of the book! Also, in terms of printing, the paper wasn't as good as it could have been. So hopefully the new edition will fix these faults. Jeremy's added some very nice content in the new edition to bring the book up to date - especially with regard to species where we've learned so much since the first edition was published, such as the Silver-studded Blue. Jeremy brought me some pupae to work from in preparation for the new edition. As we hoped, some of these became discoloured because they were parasitised - so I was able to paint the parasitic wasps from life once they'd emerged! But the printing can really make or break a natural history book, when accuracy of colours is a primary concern. I'll be going to see the new edition of the book being printed, so the printer had better be well prepared!

Pete:

So how did you first meet Jeremy?

Richard:

The idea for the book was mine originally. I'd been breeding the British butterflies for quite a while before I contacted him, but realised from various publications that Jeremy was "the man"! So I wrote to him, asking if he'd like to collaborate. He was keen and we ultimately got together, wrote the book, and have kept in touch ever since. For the first edition we wrote the book and then found a publisher - Dorling Kindersley.

Pete:

A lot of the books you've illustrated contain literally hundreds of images - how do you cope with producing such a quantity?

Richard:

The images, for example in the Butterflies of Britain and Ireland, get created over a long period of time, especially if I need to observe a species in real life. Since butterflies are seasonal and may not be multi-brooded, if I missed a stage one year, I'd have to wait until the following year to make my observations. For publications such as the Tolman guide, which only shows "set" specimens, it's simply a case of selecting specimens from collections and working from them. But the idea of illustrating butterflies and moths in their natural positions (such as many of the illustrations found in the book with Jeremy, and also in the Waring and Townsend book) is popular and has received very positive feedback. The approach taken for a publication such as MOGBI is quite academic with set specimens and formal descriptions, whereas the Waring and Townsend book is arguably more relevant to people going out and seeing things in real life.

Pete:

Rumour has it you're working on a book on micro moths?

Richard:

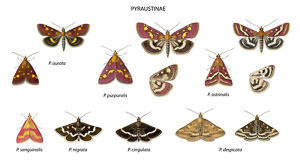

Yes - the authors are Phil Sterling, the Dorset county ecologist and Mark Parsons from Butterfly Conservation. Ever since the macro moth book came out more and more people have been asking if there would be a micro moth book - so the interest is definitely there. I originally thought the project was too daunting, having done some of the moth plates for MOGBI but, having started on the project, I can say that the micro moths are incredible things and now it's all systems go. There is so much diversity within the micros - more so than in the macro moths, you just need a lens to see most of them! Such amazing colours, shapes and postures. But I daren't look at the full list of micros - it's too daunting - especially the Tortricidae! But I'll gradually work my way through them. I've done a few hundred already, although the book probably won't come out until 2012.

|

| Pyraustinae |

Pete:

Aside from being an illustrator, you've also lead butterfly tours?

Richard:

Yes - in various countries - although not recently. But I've lead trips to Hungary, Corsica, Turkey, the Pyrenees and various other European butterfly hotspots.

Pete:

The people I've spoken to in preparing for this interview had many questions regarding your technique

Richard:

There are essentially three approaches taken, depending on the publication - formal based on set specimens, formal based on natural posture, and finally informal or natural.

With formal illustrations based on set specimens, such as MOGBI and Tolman, I always work from an actual specimen. I do a measured drawing on layout paper to start with. Everything is measured with proportional dividers and the artwork is usually done a quarter or a third enlarged. I do the working drawing and then transfer that over to the final page. For set specimens I do one side and then flip the image for the other side, so that I get perfect symmetry. I then set about painting using gouache, which is similar to water colour but isn't as translucent - it has a bit more substance to it so you can build up stronger colours. Every specimen is shown in exactly the same position, no matter how it had been set originally, with the same lighting, so that it's easier to do a direct comparison between species. If it's a plate like those in MOGBI, I just start at the top left and work my way along, and hope I don't spill my coffee over it at the last minute! Other books may digitally compose plates from a series of images, in which case I don't paint the plates as they appear, but more or less randomly or in appropriate groups. Then the publisher can lay them out as they like.

The Waring book uses a slightly different technique that is both formal but based on natural posture rather than set specimens. To do this work I use a combination of specimens and photos, where the detail is taken from the specimens but posture from the photos. But no matter how good a photograph is, you still need a specimen for the detail.

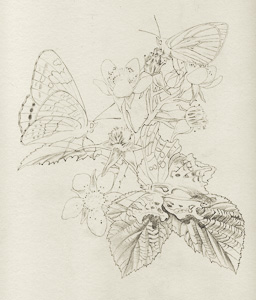

Finally, the Jeremy Thomas book uses many informal as well as formal portraits. For example, the White Admiral used on the book cover was based on a relatively poor photo taken in Bernwood Forest, but it does show the natural posture of the butterfly.

|  |  |

| White Admiral in Bernwood Forest | Initial Sketch | Final Painting |

Pete:

Do you work on multiple images at the same time?

Richard:

No - I usually just work my way through a list and get into a rhythm. I may draw out a group of, say, 10 micros - I can draw them out on layout paper and then transfer them as a group and paint them as a group. But I don't tend to dash around from image to image. I just get my head down like anyone else really and get on with it.

Pete:

It must be quite hard working in your office overlooking a garden filled with distractions, especially bird life? You must be quite disciplined.

Richard:

It can be hard. But I tend to work a lot in the evenings when there's not much good viewing on the TV - which is quite often! The main thing that keeps me going is being interested and enjoying the subjects. There's no way I'd get through a lot of Noctuid moths, micros or Erebia butterflies if I wasn't interested in the subjects! It's also interesting working through the author's descriptions so that you can look at the specimen, read the description and make your own interpretation. You might also pick up on one or two characteristics that others haven't noticed because you're sitting with the individual specimens for hours and perhaps noticing things that nobody else has. In the field, I spend a lot of time observing subjects, looking closely at how they move, how they hold their antennae, the angles of their wings - and I take a lot of photos. I don't tend to sketch in the field but the important thing is to try to get to know your subject.

Pete:

Have you ever finished a picture and then thought it won't do and start again?

Richard:

I don't really start again - you can tell as you're working away whether or not it's going well. Sometimes I go back to touch things up, but never actually start again from scratch. You can make all sorts of adjustments as you go along. You can even take the paint off with a razor blade if you need to, since the paint doesn't soak into the paper - but you have to be very careful! These days I also make use of digital technology to some extent - by scanning the images and sending them to the publishers digitally as e-mail attachments. This is much better than sending the artwork off only to get it returned damaged! If necessary, I can also tweak colours in Photoshop to get things absolutely right before sending the final digital images off for publication.

Pete:

Has your attention to detail affected your eyesight over the years?

Richard:

I do wear glasses for closeup work and use a microscope to examine very small specimens, such as micros. But any deterioration in my eyesight is simply down to age!

Pete:

What work are you most proud of?

Richard:

Probably the Field Guide to the Dragonflies of Britain and Europe, where I collaborated with a young Dutchman, Klaas-Douwe B Dijkstra. The book was a real challenge since dragonfly venation is really complicated to do. You can't really do an impression of a dragonfly's wing when you're doing an identification guide - you have to show all the detail, down to the number of cross-nodes between the veins, which have to be correct, as this may separate one species from another. Getting this right can be really time-consuming.

|

| Norfolk Hawker |

A lot of the specimens I worked from for this book were sent to me from a museum in Holland, and in quite a lot of cases they were papered, rather than set specimens and they often arrived damaged in the post. So I had to reconstruct many of them, relax them, flatten their wings out and reset them. But the book came out really well.

One book I'd like more time to redo is the Collins Butterfly Guide by Tom Tolman, since far too many unacceptable mistakes crept in with the new edition. I originally added a lot of annotations to the images that provided pointers to help differentiate similar species, but a lot of these were removed and further mistakes introduced, everything was rushed, and I knew before I saw it, it would get criticised, and rightly so!

Pete:

Would you liked to have lived in an earlier era where most guides used illustrations?

Richard:

Possibly - although most of the best guides these days are still illustrated with artwork. Even though there are a lot of good photographic guides I don't think they can capture the relevant details of accurate paintings. There is also still plenty of potential work and additional subject matter today - such as beetles and bees - although there's definitely a pecking order of popularity in the natural history world - birds being at the top of the pile, working down to wild flowers, then butterflies, and publishers may not be keen to pay to produce books on some of the more obscure groups. But I think going back to an earlier era would frustrate me with the poor reproduction available at the time, such as colour balance and registration! I'm critical enough of the publishing process as it is now and get a bit fed up with reviewers and other pontificators who are ignorant of the scanning and printing processes, which may affect reproduction in odd ways.

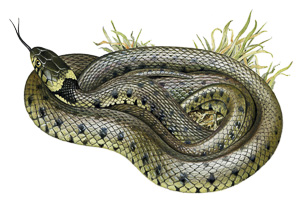

|

| Grass Snake |

Pete:

Do you have a favourite site for butterflying?

Richard:

In Europe, I guess Bulgaria is the area I was most impressed by. In the British Isles, it really depends on the habitat I'm visiting. Bernwood Forest is a good location for me locally. Also, the chalk downland on the Chilterns, such as the site at Aston Rowant is a great place if you can ignore the sound of the M40. Though it is a bit depressing when I return from abroad to see only small pockets of suitable habitat surrounded by thousands of acres of wheat.

Pete:

Do you have a favourite butterfly?

Richard:

The Orange-tip. I get them regularly wandering through the garden and no matter how I'm feeling they always cheer me up!

Pete:

So what's next on the cards for you?

Richard:

The micro moths will last me quite a while. I'd like to do a general insect field guide, which is a possibility. Other than that, some of the smaller orders of insects, such as beetles deserve greater attention. But I get all sorts of ideas by talking with people - it gives me a sense of what people are interested in and would like more information about. I attend several annual events such as the Butterfly Conservation AGM, the Amateur Entomological Society Exhibition and the British Birdwatching Fair. I'm always keen to meet people, get feedback and listen to their opinions, and even constructive criticism.

Pete:

Richard, many thanks - great to talk with you.

Richard:

My pleasure!