When I first wrote this article back in 2005, I was very much at the "end of the start" of my interest in butterfly photography. While many of the original points made in the article are as relevant today as they were back then, I felt it was about time, 5 years on, to include the additional lessons I've learned. This article is now in 2 distinct parts. The first section is an article that appeared in Butterfly Conservation's magazine Butterfly. The second section digs a bit deeper with regard to some of the technicalities behind the photos I take.

(Published in Butterfly Magazine, Issue 100, Spring 2009)

You only need to attend a Butterfly Conservation field trip to realise just how popular butterfly photography has become. As a photographer myself, I thought it would be worth condensing some of the lessons I've learned. Enjoy!

If you want to photograph a Purple Emperor, it's no good looking in a car park in central London in January. Clearly, the better you know a species, the more likely you are to find it and this includes knowledge of habitat, sites, flight times and behaviour. There are several excellent websites and books that can provide you with this information. Of course, your local branch of Butterfly Conservation can help too!

.jpg) |

| Knowing the subject - seeing the Chequered Skipper requires a trip to Scotland in early June Image © Peter Eeles |

The first thing to determine is whether your camera is suitable for taking shots of butterflies. This typically means a camera that has a "macro" mode that is aimed at making small things look large (whereas most photos, such as shots of landscapes and people, make large things look small). Without this capability, the butterflies are unlikely to be large enough in relation to the complete photo to give a pleasing result. Even compact digital cameras have a macro feature these days. The more-serious photographers are likely to have a dedicated macro lens.

Whatever camera you have, you should always feel comfortable in using it. Start with the most basic settings and progress from there. This typically means selecting a mode that allows you to "point and click". From there you can advance to more-complicated settings that involve selecting the depth-of-field (controlled with the aperture setting), shutter speed, and more.

Butterflies are not the easiest of creatures to photograph. Even if you're lucky enough to find one that will sit still for more than a few seconds, you still need to allow for some movement usually the result of a gentle breeze or the individual moving around a flower head while nectaring. Or maybe it's you moving and not the butterfly! You therefore need to consider techniques that will freeze any motion, which includes the use of a tripod and using faster shutter speeds.

|

| Using a fast shutter speed to capture Brimstones in flight Image © Peter Eeles |

Most conversations I have regarding photography seem to ignore one vital piece of equipment that has the most influence on the quality of any photograph you! Knowing your subject and equipment is not enough all of the theory needs to be put into practice. Now is a good time to practice your technique, before the butterfly season starts in earnest.

One interesting aspect of digital photography is that images can be modified on a computer. The options are almost limitless we can change composition (by cropping the image), colours, white balance, sharpness and so on. However, no amount of digital manipulation can bring an out-of-focus picture into focus and such manipulation should not be a substitute for poor photographic technique. Every photo you take should be as close to the final image as possible. Unless, of course, you prefer to spend time in front of a computer rather than taking photos!

Why is it that some photographers seem to have all the luck? My opinion is that these photographers have gone out of their way to remove luck from the equation. They are in the right place at the right time because they plan ahead. There is also an element of making an effort I personally ignore weather reports and get out whatever.

If you want to make your own luck then a great way to start is to attend one of the many field trips that are organised by Butterfly Conservation branches. Not only are you more likely to find your target species - you'll also pick up tips from fellow enthusiasts.

.jpg) |

| A Comma larva - immature stages can be as spectacular as the adults - and don't fly away Image © Peter Eeles |

One plea I would make is that you respect your environment. There's nothing worse than turning up at a site to find trampled vegetation where a floral feast once thrived. This really does detract from the enjoyment. The welfare of butterflies and their habitats has to come above the needs of the photographer.

Whatever you do make sure you're enjoying yourself. As long as your photos are improving over time, then you can feel confident you're on the right path.

The article above deliberately avoids any jargon and technical detail since it was aimed at a broad audience. In this section I go into some detail of setups I've used in the past, and the current approach I take to photography. In particular, I've organised this discussion around some of the major changes I've made over the years. Not surprisingly, you will hear different (inconsistent) opinions from other photographers. This tells me that photography is a continual learning experience and that there is no "right way" - what you're reading here is "my way"! And, of course, there's always a better photograph to be taken.

My first venture into photography started with a single lens reflex (SLR) film camera, a Zenit-E, that my parents gave me for my 15th birthday, together with a close-up adapter that fitted on the front of the lens.

|

I remember using it to photograph the commoner species, and still have photos taken with it, including Orange-tip, Puss Moth, Emperor Moth and the like. But the photography went on the back burner for many years as I focused on my A levels, university and then family. Although, I have to say, the interest in butterflies never disappeared - I have a vivid memory of a Swallowtail emerging from its chrysalis in the university's halls of residence which caused some excitement! That latent interest in studying immature stages has always been with me - and from a very young age.

But several events all combined in the late 1990s which brought my passion in Lepidoptera back to the fore. First off, my young family was not so young any more, and I had a little more time on my hands. Secondly, there was an increasing interest in conservation, a topic that I was passionate about having seen many of my old haunts disappear under concrete. Lastly, the digital revolution had reached photography and while digital cameras were still relatively-expensive when compared with their film equivalents, I knew they were here to stay.

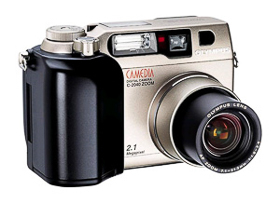

My first digital camera was a compact - an "Olympus Camedia 2040 Zoom" model. It had, by today's standards, a tiny resolution at just 2.1 megapixels (my mobile phone has a higher resolution today!).

|

But this camera opened up a whole new world for me, for reasons that are well-documented. I could see my images immediately and easily alter them to some extent (such as cropping the image to give a more-pleasing composition). Being able to take more pictures without incurring any additional cost was also a bonus. I could review my images in the field and adjust the camera settings if needed.

However, I've also come to the conclusion that taking lots of photos, because I can, is no substitute for trying to get the shot right in the first place. One good shot will always be better than ten average shots!

In 2004 I took a trip to the US and, attracted by the exchange rate, decided to buy my first digital SLR - a Canon EOS 10D (6 megapixels). Although this model has been superseded many times since, it's still a nice piece of kit and can produce great images. Which brings me on to another point.

Many photographers focus on their equipment, rather than their technique, and yet it's the technique that makes the biggest difference.

Along with the 10D I also bought another essential piece of equipment for those interested in photographing Lepidoptera - a dedicated macro lens. I still have the Sigma 105mm macro lens I bought all those years ago and still use it now and again. I also have a ring flash which also comes out on occasion.

|

There is a wealth of information on the basics of photography which I'm not intending to reproduce here (you should get a basic understanding of apertures, shutter speeds, depth-of-field and ISO settings, for example, and there are many good online resources available to help in this regard). However, I would like to point out some of my own observations that are specific to butterfly photography.

So here is the challenge: how can we freeze movement while retaining a good depth-of-field, so that as much of the butterfly as possible is in focus?

All of the options mentioned in the table below are aimed at addressing this apparently-simple question. Unfortunately, there isn't a single correct answer and different techniques might be appropriate on different occasions. Here's why.

Firstly, we need to understand what "movement" needs to be frozen. There are basically 2 elements - the subject and the camera. With regard to the subject, butterflies are often constantly on the move and even if they're still, the plant they're resting on might be moving. With regard to the camera, the photographer may be moving (unknowingly!) and, in extreme situations, even the movement of the shutter can result in a blurred image. Secondly, we also need to say something about achieving a good depth-of-field. Strange as it may sound, a greater depth-of-field is achieved when using a smaller aperture. Conversely, the wider the aperture, the less depth-of-field is achieved.

So let's now put all of this together. The table below shows some options and both the positive and negative results. This is the list I typically describe to people when they ask me for suggestions on how they might improve. This list has been learned the hard way but I hope gets straight to the point for those wanting to take better butterfly photos.

| Action | Positive Effects | Negative Effects |

|---|---|---|

| Increase shutter speed | Freezes any motion | Aperture needs to open to allow sufficent light onto the sensor, thereby reducing the depth-of-field |

| Increase ISO setting | Allows a faster shutter speed to be used for the same aperture, which freezes any motion | High ISO values result in "grain" on the image |

| Use flash | Allows a faster shutter speed to be used for the same aperture, which freezes any motion | Can produce unnatural-looking images |

| Use a tripod | Freezes any motion caused by the photographer | Can be cumbersome to set up |

| Use a remote release cable in conjunction with a tripod | Freezes any motion caused by the photographer and the camera shutter | Can be cumbersome to set up |

| Decrease aperture | Provides a greater depth-of-field | A slower shutter speed is needed to allow sufficient light onto the sensor |

One thing is clear - getting a good photograph relies on an appropriate balance of many factors and only practice will make perfect!

Moving beyond the technology, there's also something about photography that I really didn't appreciate until I started looking at all of the wonderful shots being contributed by the UK Butterflies membership. That aspect, I realised, is that photography is an art form. Areas such as composition and colour are elements that have recently come into play in my photography, and I have a lot of learning to do!

Having obtained "record" shots of all of the British species, my focus is now on image quality. At the present time, my standard setup is a Canon 30D with a Sigma 150mm macro, mounted on a Manfrotto 190CXPRO4 tripod with a Manfrotto 488RC2 head. As long as there is sufficient light available, I can get pretty decent results without resorting to any form of flash. And, of course, I've yet to take my best photograph!

|